William Hooker Continues Proving That the Fringe Is Still the Center | The Sharp Notes Interview

- ezt

- Apr 23, 2025

- 26 min read

Hooker Talks Free Jazz, Vinyl as Artifact, and a Life Made in the Margins

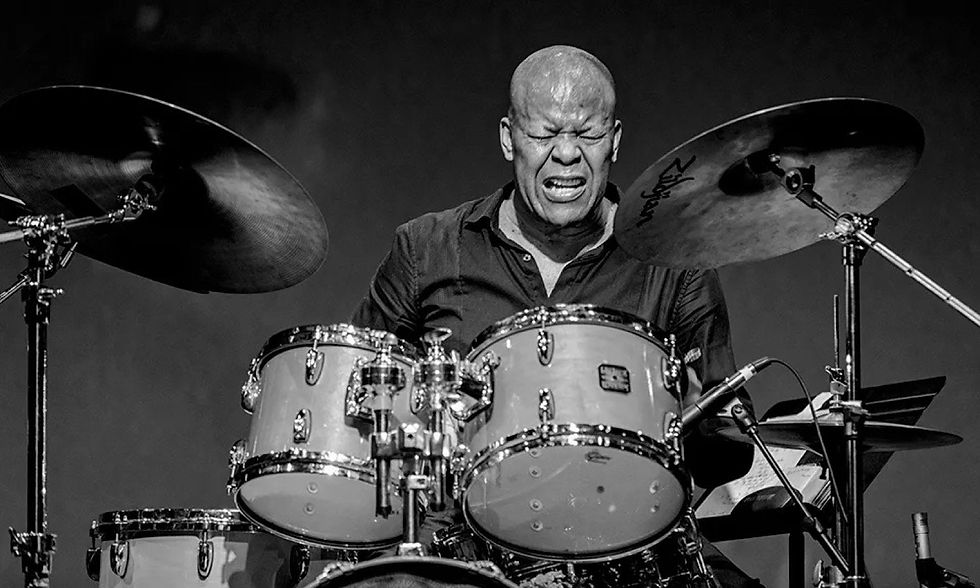

William Hooker has spent decades making music on his own terms—loud, unflinching, and fully independent. A drummer, composer, poet and more with over 70 recordings as a bandleader, Hooker is a fixture of New York’s experimental underground, shaped by the Loft Jazz scene of the 1970s and carried forward through venues like CBGB, the Knitting Factory, and Roulette. His latest record, Jubilation, recorded live at Roulette in Brooklyn, is another chapter in a career defined by pushing boundaries, building community, and resisting easy categorization.

The following conversation with William digs into both the record and the mindset behind it. Hooker speaks plainly about what it means to work outside the mainstream—how playing free jazz often means playing for people who don’t yet know how to hear it. He talks about rehearsal as a way to build trust between musicians, about improvisation as a response to the space you’re in, and about the value of taking creative risks without overthinking them.

Throughout our chat, Hooker is generous but direct. He knows what he’s doing and why. He’s not selling a product—he’s sharing a process. There’s no mythologizing here, just decades of work and clarity about what matters. Jubilation isn’t a throwback or a statement piece—it’s just where Hooker is right now, doing what he’s always done: leading from the drums, assembling the right players, and trusting the moment to shape the music. In a city that rarely makes room for artists to grow old and stay weird, Hooker is still here—evolving, documenting, and finding joy in the chaos.

ezt: Maybe this is an interesting way to start the chat. Do you think of New York as impacting your music, and your composition, and your way of thinking, and even just sounds? Even just the sounds of the city, thinking about your work. Do you ever feel inspired by the town? Certainly, you must, after being there for so long.

wh: Yes, I feel that way, but I knew at a certain point this was the only place that I could find people like myself, thinking like me, and were really aspiring to trying to play the kind of music that I play. More or less, we had to be here, otherwise, I don't think that there are people like us in a concentrated place like that. Even in certain cities, you can go in San Francisco, you don't find this. You can go in Chicago, you don't find this. Now, I can walk right outside, and my friends are right outside, and the studio is outside. It's really because of things like that that we wound up making this our home. It wasn't something that was guided by the spirits or whatever. It was very practical. Very practical.

ezt: It's interesting too, I just spoke with Michael Dorf, who was the Knitting Factory guy just a few weeks ago, and I thought to myself, this is like a New York music--

wh: How did you happen to call him? What was that about?

ezt: I was interviewing him about this upcoming Patti Smith tribute that they're putting on at Carnegie Hall next month, and he's putting a thing together. I said, "Sure, I'd love to talk to him." I was interested just talking about his history with the Knitting Factory and City Winery, and I know you did a lot of work at the Knitting Factory.

wh: Good friend. He's a good friend. What can I say? Obviously, you said I was talking to Michael Dorf. I laughed because that's the kind of relationship we have. It's like that. It's something that you meet somebody and they never change in your eyes. You just remember all the good times and the things we've done for each other.

ezt: Can you talk a little bit about playing music in New York City back then in those days, and what it's like now? It's so much different. I'm a musician too. I'm coming from a little bit of a different place, but I remember in the late '90s we would do a lot of things. It was a much different environment for me, but you going back to the '70s and the '80s with the Knitting Factory, and looking at it today, how do you see the music world now in New York City?

wh: I came in here during the Loft Jazz era. Because of that, a lot of the places that I played, I don't even know if you remember them. We're playing improvisational music, mostly coming from a Black place and coming from a place of the history of the music, and great, great, great musicians all played in all these places. This was a separate thing from the Knitting Factory. It was separate, but it happened at the same time. This was called the Loft Jazz era. I also played at CBGBs a lot because obviously, I was the other part of improvisational music, which included all the people that were surrounding-- what was the guy's name at CB's? I forgot his name.

ezt: Hilly Kristal.

wh: Of course, Hilly. Yes. Hilly, and all those places that were around in that area, too. I played at 14th Street, and things like that. I had my feet in a lot of different areas, and obviously, with me being around the Knitting Factory a lot, that was a whole other scene. Each place had its own little scene, but I was in all of these scenes all at once.

ezt: New York City's so different now. There was a certain vibe to the city back then that has changed. Things are so much more corporate now, and of course, a lot of the clubs that we're mentioning, I'm sure, are no longer there. What about now? Do you get that same vibe? Can you find that same tap into the Big Apple, musically speaking?

wh: Yes. I think you can in a great way because we have organizations like Arts for Arts, for example. They're doing a continuous festival all the time, and this is separate from places that are basically rental spaces. Like, for example, a Roulette, you probably know of, right?

ezt: Is that where you recorded this record?

wh: Yes. I've known Jim Staley forever. He lives in Manhattan. He lives right down the street from David Sulzer, and David Furst was around that area. There are a lot of people-- because we're talking cross genres, we're talking a lot of different things that are all happening at once. You got to remember. I don't know. I just was able to navigate all these different places all at once and put it into my music. The whole economics of what it takes to

live in New York and all that stuff.

Donna (Williams wife): Housing.

wh: I thought--

ezt: Housing.

wh: All right then. She says housing, housing.

ezt: Yes.

wh: Yes, that's important. We've been in our place for 50 years, and it's rent-stabilized. Because of that, a lot of things that people talk about I understand it, I get it, and we've advocated for it, but I don't know, you just roll with the times. You roll with the times. You roll with who's ever in power in a certain sense. Music-wise and the music I play, it doesn't roll with who's ever in power because they never liked it really when you really think about it. This is not like a changing from the Village Gate to Le Poisson Rouge. This is a different thing. I don't know. You have to think alternatively if you want to really get into what I'm into, I think you're ready for that. [chuckles]

ezt: I'm ready. I'm ready. It's interesting and free jazz, if that's what we want to call it, if that's what we're talking about here, I think a lot of people love this concept of free jazz, and it does take some time to get into it. You have to be open to it. Sometimes I think about it like trying something adventurous on a menu at a restaurant like, "Hey, let's try this thing. This isn't something I usually have, but let's do this." Have you ever been in a position where you've-- not that you've probably ever wanted to convince anyone to listen to you or anything like that, but because you've got your audience, but how do you explain to someone what you do, or people that you really love what they do in that genre to someone that really just doesn't. It's something new to them. It's something that they need a minute. How do you approach someone like that?

wh: My first thought that came to mind is I use a person like you, because obviously they trust you. They think you have a knowledge of music overall that they will accept easily, and you can converse with them on a one-to-one level. For me, a person like you is a great intermediary between what I do and what they are expecting, because what I'm giving, they have no clue about, for the most part. How could they expect anything? Then when it shocks them to death, then they wind up either liking it or hating it. It's not a matter of-- No, I won't say that. They can grow into it, that's for sure.

Most immediately, I think that that's the importance of the role that you fulfill because you are really a person that can speak to them, the audiences, the venues, to let them know just generally what are the times doing, what's the sign of the times here? I have a difficult time explaining that because I'm really going so fast that I may be talking about something that hasn't even happened. They haven't even caught up with yet what's way in the back. It's both a job for you and me to do.

ezt: I always think, I always tell people, music like this is something you put on. It really can clear out your preconceptions of music. It's like a great-- if you wanted to compare it with someone, people love the idea of a detox. Detox. We're going to detox and whatever detoxify. I think sometimes putting on a record like this, it really detoxifies where you're at, where your head is, and it reboots you and resets you to go, "Oh, okay, now I feel balanced again." That's how I feel personally. I think that's an interesting way to share it with people, too.

wh: That's good. It all depends on how open-minded these people are, because you got to face the facts that a lot of people, they have to detox from Jon Lucien. Let alone-- Really. Seriously. Seriously. You have to really think about--

I'm telling you, you got to, "Well, what is that?" You got to say that and feel comfortable in saying that. I think that familiarity and respect for people is a good thing. It's just that at certain points, I'm almost as if something that people feel, I make the music, but I don't really converse with them about-- I don't get the opportunity that much to converse with them about what the music is about, who is involved in it with me, how do we get it over to people, what it takes to practice it, what it takes to learn it.

They're not interested in all that. I think that they wouldn't even ask you that question, but the questions they ask you, you are my introduction to them. That's the way I feel about it.

ezt: One of the unique things about the album is there are some spaces and there's some emptiness that surround a lot of the arrangements. I think the listeners' mind, at least my mind, naturally fills in some of those gaps. I noticed this with linking, which is really Adam Lane on Upright Bass, and similarly on "The Stare", where there's this sense of other musical elements or sound that are being assumed or almost imagined. Does that make sense to you? Do you share that experience where the music is leaving room for the listener to fill in what's missing there?

wh: It always does. I think that life does that as well. Not just musical links. You could be reading a great novel, and your mind, just all of a sudden, conjures pictures of what you're reading. This is the same kind of thing in a sense. That makes total sense to me. It's just some people like things a little bit more explicit. I'm not really necessarily like that. I trust in something that's bigger. I trust in a bigger intelligence that can speak to them and speak to me at the same time, and can cover us all. Maybe that's what I mean.

ezt: Talk to me a little bit about the title Jubilation, which I thought about a lot while I was listening to it. Sometimes I'm feeling jubilation, sometimes I'm feeling something celebratory, particularly on the second side, I felt that character. What inspired you to choose that title? How do you feel it represents the overall mood?

wh: Happiness. New music and new jazz don't necessarily always conjure happiness to people. Sometimes it's about struggle. Sometimes it's about social inequities. Sometimes it's about pure chaos, or sometimes it's about an abstraction that nobody can really understand. For me, on a simple side, to make it as simple as possible, I'm just talking about the happiness that we brought to each other and brought to the space that we played it in.

That's another thing I want to elaborate on because we try to bring that to every place that we play. It just so happened that that's what really happened. That's why I called it that, because it revealed itself to me, and it was a good thing.

ezt: On Davis brings a really unique perspective to a lot of those tracks. What's it like collaborating with him? How do you see guitar contributing to the sound that you were shooting for on this album?

wh: My relationship with the guitar goes way, way, way, way back. Shambala is me and Guitars. I don't know if you've ever heard Shambala.

ezt: I think I might have when I was checking out your catalog.

wh: I had Elliot Sharp and Thurston Moore on it. Those are two individuals that also play guitar. I've had Jesse Henry, who's now a-- He was one of the starters of the Black Rock Coalition. I've recorded with him and his group of people. I'm trying to think of all the other people. I've recorded with a lot of guitarists, and Lee Ranaldo, who we toured Europe together. It's just that now On was the person that was brought in for this particular project, and we've worked together maybe a long time.

He fit in exactly. His way of looking at the music is very good because he doesn't try to overshadow it, doesn't try to play so loud that it's only just a guitar group, and he listens to other people's music because he understands that other people are up there with him playing. That's the main thing I can say. I think I chose the right person for this album. I'll put it that way.

ezt: How about the other folks? What's your relationship with the other folks you were playing with on this record?

wh: Do you know any of them?

ezt: I don't know them, though. I might know them from the album jacket here.

wh: Matt Lavelle.

ezt: Matt Lavelle on trumpet.

wh: That's right. He plays a lot of things. Plays trumpet, plays English horn. He is a person that was living for a very, very long time in Manhattan. Moved to Philadelphia. Now he's a essential part in the Philadelphia scene. Also, Stevie Manning, who now is located in-- I think it's East Hampton. Learned to play music way up there. I've known her for quite a while. We've done stuff all over the place. I-beam and Roulette, and The Kitchen. Adam, I've known for quite a while. Really, what happened was I brought them all into the studio, Funkadelic on 40th Street. We practiced, and then the gig came along, and it just so happened I wanted to do a bang-up night. This is what came from it.

All these people, I got to say, I played with them a lot. I played with them really a lot. It'd be crazy for me to try to figure out little places and all this. I just know them as the people that I know. They're all located-- They were all located in Manhattan, which was the good thing about it, because then we could practice a lot.

ezt: Sure. It's convenient. Tell me, how do those practices go? How do these arrangements take flight? What does it look like? What's the secret there when you guys get together and you approach these songs and these concepts? How do you figure out how this is going to roll?

wh: You go into a room, and you make sure that the lighting is fine. You make sure that the microphones are okay. You make sure that nobody's going to bother you for at least a couple of hours. I get there usually early, and I put the music out, and we first get there and we practice. We just play. We don't even play the arrangements. We just play. We just improvise because I want them to get to know each other. I know them all. I don't know if they know who the other people are in the room.

By doing that, they hear a distinctive sound from the person. Then maybe those people will communicate, and then other people will communicate. Then, after you do that for a while, you stop. Then I break out the music. The music has different titles. I explain to them what the titles are, explain how we're going to do it, the arrangement of it. Then we try it and we see if the people can get as close to memorizing it or being very comfortable with it as much as possible so that there's a intertwining of the comfort that they feel in the music and the comfort that they feel with each other, and the individuals playing their own instruments.

You got to remember, they're all coming from different places. It's just a matter of everybody getting in tune with what that room is going to say to us. Then, after you've done it, maybe I have to do it two or three times, and then we go and play, realizing what the thing is about, because each time you play, I have to go to Roulette to make sure everything is set with Roulette. That's separate from the musicians. They're a part of it, too.

Then that's the magic that it is. I think it's a very practical thing. It's very practical, but the only thing that isn't practical is what they are going to play. That's where you get into the mystification of it. Basically, if you have them in the right room, they respect each other, they're all comfortable, the lighting is right, the sound is right, the drums are right, and I'm there early so I can give them the music, what else can you ask for?

ezt: In those rehearsals, the improvisational nature of this music, how do you-- Let's say, in the rehearsal, it's going great, everything's good, but then somehow in the actual show, there's a shift or a change, or as you say, the space can influence-- you guys get comfortable in a rehearsal space, but then when you get to the real space, it's a little bit of a different feeling. As the leader of the group, how do you nudge that along even during the performance itself?

wh: You go along with it. You go along with it, and you roll with it. I think that's the nature of improvisation, being able to answer a call that you never expected. I think that's the nature of it. It's almost like opening a curtain. You don't know what's behind the curtain. Then, when you open a curtain, you see it and you say, "Oh, okay." Then you just go with it like that. It's nothing. I don't look at it as something that's earth-defying or anything like that. Maybe because I'm used to it, and I think that the people I choose, they're like that as well. I don't like too much mental dilemma all about it and all this, and trying to answer it in terms of academics.

You leave that at the door, you really do. You leave that at the door. You come in and you just try to communicate with the other people in the room. To tell you the truth, if you go to the space and that doesn't provide that, you try and figure out what is the space providing. Maybe I can change to whatever the space is providing, or maybe I can't. Maybe I can't. That's just a one-off. You look at it like that. It's not as if you're always shooting for perfection, because a lot of times in improvisation, you don't know what you're going to get. It all depends on how people's minds are, how my mind is, what their health is like, and how they interact with each other, and all this without getting into too much mental-- what would you call it? Debate. Mental debate.

ezt: For some musicians, that would be really the most terrifying thing in their career, would be sort of, "Oh, well, let's open the curtains and see where we go."

wh: Yes, but I've done that so many times, it doesn't surprise me anymore. Really, it doesn't surprise me. Not at all. It really doesn't. It is not like I'm waiting to open the curtain. It's just that if it opens, it opens. If it doesn't open, that's okay too. Yes.

ezt: Why not? Sure, we could do this.

wh: Exactly, exactly, exactly.

ezt: It's interesting to hear you talk about the space. I don't think I've ever heard someone-- When you're talking about the space, it makes me feel as though you're almost saying that the space is almost a player or almost an instrument in the ensemble itself, that the room, for better or worse, it's going to impact what's happening here.

wh: Yes, I play drums. Every drum set that I walk into, I have to deal with it. Some people play piano. How many people do you know carry a piano on their back? When you walk into these situations, that's what I mean. The room includes drum sets, the room includes pianos, the room includes all these things, separate from if the microphone works, that's a whole other thing. All of these things, what can I say, I've done this many times, and I enjoy it. I really enjoy it. It's a good feeling to know that you're getting ready to do something artistically, and it involves a lot of different aspects of myself and the people that I'm playing with. It's a joyful meeting, I'll put it that way.

ezt: You had your own podcast there for a while, and you're so fun to talk to. I'm wondering if you have thought about-- I think you haven't really done any new episodes in a while, but have you thought of returning to that or doing anything with that again?

wh: I'm glad that you brought it up because you and I will be the very first one that we do. You'll be the first person, along with maybe one other person, and we will do this. We will do this. Seriously.

ezt: I would love to.

wh: It's just that a lot of times, you do things and they last for a certain amount of time, and you don't go back to them because the time isn't right to do it, or you wanted to meet a whole new group of people. I made a film of the podcast, and you may not have seen it.

ezt: No, I don't think I did.

wh: It's called The Lost Generation - Outside the Mainstream. It's an hour and 45 minutes long, and it has premiered in five different cities. New York, it was an anthology film or archives. It was in Seattle. It was in San Francisco. It was in Hartford, and we got the opportunity at Olympia, I believe. It's a regular movie. The movie's been out for a while.

ezt: That was the name of the podcast was Outside the Mainstream, right?

wh: That's right, man. Yes, but the thing about it is, if you remember, all of those interviews were about 40, 45 minutes long. This was all edited down. I used people from NYU, students. They all volunteered. I gave them a grade where I had 10 or 12 students. We all edited all of those interviews. Someone else did all of the putting together of the movie. The movie was premiered at the Vision Festival, one of the main nights, along with another movie called The East. It was in The Wire, it was in Downbeat. It was all over the place. That's another thing I haven't turned you on to.

ezt: If you reboot the podcast, you'd potentially get another film work out of it?

wh: No, no, this all depends on the people, because some of the people have even passed away. That's the reason why I think in a different vein. Times change with the people that are alive to be around as witnesses. I'm around a lot of new people, and a lot of the questions are the same, a lot of the questions change. I haven't thought about it, but I'm thinking about it now. I haven't thought about it for quite a while, along with dealing with silent film. I really like silent film and playing to silent film as well. That's a whole other vein of what I've explored. As a matter of fact, part of that movie, Michael Dorf is in the movie.

ezt: Oh, no kidding.

wh: He didn't tell you?

ezt: No, when I talked to him, I don't think I knew the connection, so I didn't bring it up.

wh: It was fun. It was fun for me. I think it was fun for him, too. You should call him. Yes, serious.

ezt: I will. One of the things about your album, I wanted to ask you about, a lot of the tracks really feature individual instruments performing solo. There's not a whole lot of collaboration, at least on this album, where people are playing together. Is that something that was part of the arrangement, or how did that conversation go? How do you leave space for everyone? How does that arrangement go?

wh: I get your question. It's a good question, too, because you got to remember, you probably have listened to the vinyl.

ezt: I did.

wh: The CD is different.

ezt: Oh.

wh: The CD is an hour.

ezt: The record's edited down to probably about 40, 45 minutes or something like that, the record.

wh: That's right. That could be part of it. That could be part of why it's the way it is. I think that they did a great job with that, but each format is a little bit different. I like each format, but if you really want to get a full taste of it, you have to listen to the CD because there's much more material on it. That's a whole different thing. What I was trying to do, really, was give-- because this is my fourth record with this label, and each record is different. Each record is different. I think I was just trying to give them an overview of what Jubilation means in terms of this particular quintet, because each record has a different group on it.

As you look at the progress that's happened with all the records, you can tell that this fits into one of the four. That's the way I was looking at it, and I think it worked. Let's put it that way. I think it worked for those people that really, intentionally, want to see how things progress. You know what I mean.

ezt: Yes, but that takes some planning. That takes some thought. It takes some creative thinking to have the foresight to link up a-- It's almost like they'd all work together in a box set or something like that, it sounds like. I haven't heard all of the others.

wh: All right, then. Good. That's the whole thing. I think that you can even go into it and just pull out some tunes from each one. That's one thing I would suggest before you ask Andrew to give you some free records.

ezt: Send me the rest of them, Andrew!

wh: See, you got to talk to Andrew about that. Andrew's cool.

ezt: I know how to do that.

wh: All right. You've been working with him for a while. See? He's cool.

ezt: I have. He's a cool guy. It's a great label. They're really doing some fantastic stuff now. I've done a lot of writing about them and a lot of interviews with his artists, and they're really an interesting label.

wh: All right. Yes.

ezt: They really are. We talked about film. We're talking about music, of course. You're talking about podcasts and different ways to use audio. As I understand it, you've done some experimentation with electronics and turntables, and we're talking vinyl here. Could you just tell us a little bit about what that work has been and what vinyl means to you? How do you think about its resurgence here in the 21st century? We're talking about your last few records coming out on vinyl, which probably hadn't happened in a while.

wh: Now, that's a good question. That's a long question. I've been lucky to deal with some people that really understand and love vinyl. Two of them that come to mind, automatically, are Christian Marclay-

ezt: Thurston Moore.

wh: No.

ezt: Oh.

wh: DJ Olive. That is their instrument of choice. That's their instrument of choice. They have as many records behind them as you have behind you, and they play turntables. That's what I'm saying. Being around them, it changes my whole perspective about vinyl and being able-- You call it a turntable list? What do you call it?

ezt: Yes, turntable. I guess people say that. Turntablism.

wh: Yes. It's a different vibe. It's a different thing altogether. A lot of times, we learned from each other because I don't know that much about what they do, and they didn't know that much about what I do. We found out that we make music together, which was really good. What was the second part of the question, though?

ezt: It's interesting you've seen vinyl, we're talking about New York City in 1975. Of course, vinyl was the way to consume music, but now you're seeing your music being released on vinyl again, and you know it's a thing here in the 21st century. I'm just curious how you feel about that evolving back to that?

wh: It's okay. I have no problem with it. It's just that my understanding of the vinyl art is completely different than people who respect a vinyl record because the people that I spoke of, they only use it in terms of-- I won't say what hip-hop people do, but they only use snippets. They're trying to make a whole universe out of snippets off of all these kind of records with all these kind of genres. It's not like they're putting on one record and listening to it from the beginning to the end. That's a whole different thing.

I'm really, really glad that they put these records out on vinyl because to me, they have a different perspective for the eye, you look at the record, you say, "Wow, this is something." You can read the notes. You feel as if you're handling some artifact in a way. It's a little bit different. I think that it's a very, very good direction that we're heading in as far as that goes. I respect it, and I respect people who try to make people aware of the fact that all this music that they're getting, my music has that option for them. I'm really glad that Org is doing that. There's no doubt about it.

I still have a lot to learn about it. I'll put it that way. I have a lot to learn because many places don't afford being able to handle an artifact like you're handling a rare book. They don't do that. They don't think of it like that. They don't believe that a scratch on a vinyl record is that important. You know what I'm saying?

ezt: Yes.

wh: That's part of the experience, as you know. That's part of the experience. That part of the experience, "No, it's got to be super clean. It's got to be up here," not really. Not really. Now, when you really get down to this precious thing you're putting on there, then really you're satisfied, you're happy. Look at you, your face, you're getting all smiley because you understand that.

ezt: Sure. I'm thinking of a lot of the records behind me are-- as I said to you at the beginning of our conversation, I got when I was a little kid, and of course, I have memories. In fact, I have one record that I remember I had out on the floor when I was just a kid, I must have been 9, 10 years old, and my dog was running around, and he ran across it, and scratched it, and ripped the sleeve. I still have that sleeve. That's not perfect, it's not pristine, it's not mint, but boy, that's a story that I can show my kids and say, "Hey, this is an actual claw mark from my dog when I was a kid."

wh: This is what I'm saying. This is what I'm saying. Everybody that deals with this, we all have stories, and it's very touching, it's very intimate, and it's very personal. That's a good thing because everything doesn't have to be mass-produced, except when you start thinking about the price of it, then it gets into another level. Seriously, it doesn't have to be all uniform, just stamp it out, put it out, and then in four months, do it again. It doesn't have to be like that. It could be really a special experience. That's what this is. I'm really happy about that. I'm happy about that.

ezt: I hope no dogs run across your record.

wh: What did you say, Donna?

Donna: They're very special.

wh: Oh, she said LPs are very special.

ezt: They are. I'm glad I don't have a dog.

wh: Wait a minute. Come here, Donna. Wait a minute. See? No. Hold it. Wait. No. She says, "Oh my goodness."

ezt: Oh boy.

wh: You're saying something that I wasn't even thinking about.

Donna: I don't know how you could not think about it.

wh: You're right. I don't know how I could not think about it with my son-

ezt: Good thing Donna's there.

wh: -all of my record covers, all those for the Knitting Factory, my son did.

ezt: Oh.

wh: My son did it. He did every single one of those records; Thurston Moore, Lee Ranaldo, Jason Wang-

Donna: He did drawings.

wh: -he did all the drawings.

ezt: Oh, well, there you go.

Donna: They're always very special. You always handle them with such care. They have the album art, the information inside. You can't even compare.

wh: See?

ezt: There you go.

wh: Can't even compare. See? I'm telling you...

Donna: You used to handle it very carefully.

wh: I did, Donna.

Donna: Again, I don't know what you're talking about, scratches...

ezt: You made sure that nothing had scratches. Do you still have those records?

wh: Yes. I have the vinyl pressings. Let me show you something.

ezt: Go ahead.

wh: No. Where are they? Wait, Donna. Hold on. Obviously, you know what this is.

ezt: I know that. I got one right here. See, I got the same exact thing here.

wh: All right. Then, see? You don't know what this is. (William shows me a few records in non-descript sleeves).

ezt: It's a test pressing.

wh: That's what I mean. You see? The thing about it is, you don't know what this is.

ezt: No. That's another--

wh: See what I'm saying? I'm telling you, this is the very first meeting of a long-- See? I'm telling you. I got some stuff.

ezt: I know--

wh: These are the evolutions of what it comes up to before it gets to this. You see? A lot of people don't know that. They just think that you walk in, you see this thing, you get it, and it's all set. They don't know it goes through this whole gestation period. They don't get it. It's really a good thing.

ezt: That's the drum ensemble you were talking about before?

wh: No. I'm not even going to tell you what that is.

ezt: Oh, okay.

wh: I'm not going to tell you. It's special. Once it comes out, you're going to see because I'm going to tell you, "Remember that record that had the red label?

ezt: Yes.

wh: That record," and you're going to say, "Oh snap. That's what it was."

ezt: That's it, though.

wh: I'm not going to tell you yet. I'm becoming very lucky this year because three records are coming out, one right after another, just like that.

ezt: That's very exciting.

wh: Yes, it is. To know that there's going to be different groups playing in different places, and it just all builds up. That's what it's about. Luckily enough, these are in all different formats, but the main one we're talking about is Jubilation right now.

ezt: That's right. Are you doing anything in particular to support this record now, aside from interviews like this, but musically, how does that work? What does that look like?

wh: There is a series that's happening in Manhattan, and the series is called Basement. It is being done at the Artists' Places or Artists' Site. I forget. It's on Cortlandt Alley. I know that. You go into this street, and you go into this place, and it's like an alley. It's an alley actually, but when you walk into the space itself, then you see-- You get to the space itself, and then you walk deep into it, and then all of a sudden you're in this cavernous space that has a DJ, it has a place for dancers, a separate section, and then our group is going to be featured. It's going to be the Jubilation Night.

ezt: It'll be the players on this record?

wh: Yes. They're coming in from wherever they are. As I was telling you, that's part of the little problem because they have to come in from four hours over here, two hours over here, and we have to practice and at least play. This is a setup. I was waiting for this to happen, too. How could I do this? How could this happen? How could these guys walk home with a feeling of great joy, and some money in on it, and their tickets taken care of, and all this? That's what's going to happen.

I'm shooting for other places now to find out what other places are going to be open for this situation, but that's the first one. Another thing I think can happen, and I'll find out from Andrew how it can happen, let's see where else we could take this, because it might be easier for me to go and do things with a trio, with a quartet, whatever, but to push this particular record, because I'm proud of this record. I really like this cover.

ezt: Where's the cover art from? It is a really cool album cover.

wh: It's this guy Dean Norson, because we went through about four different artists to reach this one, because I wanted to make a turn with the Org Music people and each other one had my face on it, or whatever. This one, it turned the corner, which shows that we're going in a different direction with this. You could tell. If for any other reason, just because of the eye, you could see like, "Yes," different than the other records, with me on the front, and now this is made in a whole other-- That's one thing that Andrew and I were really seriously trying to do.

ezt: It certainly echoes the vinyl record shape and size, too. It's saying there's this circular mystery inside...

wh: I know, but you see where the red is? See?

ezt: Yes.

wh: See how the red penetrates, and it goes-- It's different. It's just different. I really appreciate the care that they took, I really do, and whoever they found, because I didn't know those people. Those are people in the West Coast. It worked. It really worked. I love this record.

ezt: Oh, cool. William, I thank you so much for your time today. This was a really fun conversation.

wh: I think so too.

Comments